Ernest Dowson

Ernest Christopher Dowson (2 August 1867 – 23 February 1900) was an English / British poet, novelist, and short-story writer who is often associated with the Decadent movement[1], alongside writers such as Oscar Wilde. Dowson was a lover of young girls, and expressed his deep feelings for them in several of his poems, notably those from his three collections Poésie Schublade, Verses[2], and Decorations. More insight can be gained from his correspondence, namely The Letters of Ernest Dowson (1967)[3] and New Letters from Ernest Dowson (1984).[4] These sources are used throughout this page, as well as quotes from Agapeta, and often include French phrases as Dowson spoke the language fluently.

In 1889, aged 22, Dowson became infatuated with an 11-year-old female, Adelaide "Missie" Foltinowicz, the daughter of a Polish restaurant-owner. In 1893, he proposed to Foltinowicz, who was then aged 15, but was rejected. She later married a tailor who had worked at her father's restaurant, Augustus Noelte, in 1897. Dowson was a member of the Rhymers’ Club[5] (London) with W.B. Yeats and Arthur Symons, and the love / infatuation he felt for Adelaide inspired him to write poetry, some lines of which he is now best known for. Dowson lived an active social life but also lived mostly in poverty, eventually suffering the death of both his parents. His father suffered with tuberculosis and killed himself with a drug overdose (chloral hydrate), while his mother, who had a history of what would now be called mental illness, subsequently hanged herself after contracting the same disease. Dowson's life was marked by ecstasy and despair, with his poems reflecting the themes of childhood and unrequited love, being the source of the phrases “gone with the wind” and “days of wine and roses.” After returning to London to live with the Foltinowicz family in 1897, he was found virtually penniless by writer and Wilde biographer Robert Sherard in 1899. Sherard took him to live at his cottage, where Dowson spent the last 6 weeks of his life, dying of tuberculosis at the age of 32. A few years later, Adelaide died of a botched abortion in 1903.

Before he met Adelaide: Dowson and Minnie Terry

Through his poetry, letters, and stories from his friends, scholars and commentators have inferred that Dowson likely had sex with post-pubescent females (likely prostitutes), but is known to have preferred the company of pre-pubescent / little girls. Before he met Adelaide Foltinowicz, Dowson was a devoted fan of the child actress Minnie Terry, then aged 7 (she was born on January 1, 1882). Dowson watched all plays in which she acted, collected her photographs and various souvenirs about her. He nicknamed her “Mignon” (for her role in the play Bootle’s Baby), “la petite” or “la chère petite”.

Dowson wrote in The Critic, dated 25 May 1889, a review of the play A White Lie, praising her perfection and spontaneity in her role as Daisy Desmond, even saying that at a critical moment she saved the play from the false note of an adult actor. A famous contemporary of Dowson, Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) - also an avid theater-goer - did not share his enthusiasm for Minnie Terry.[6] Dowson wrote in The Critic of 17 August 1889, an article entitled “The Cult of the Child”, stating that children under 10 have by nature superior acting capacities, while among adult actors such talents are the exception. He cited Minnie Terry’s role in Bootle’s Baby as an example.[7]

Ernest Dowson as a MAP (Minor Attracted Person)?

Dowson's adoration of little girls was exclusive: it did not extend to post-pubescent females. The fact that girls grow up into adulthood frightened him, as he wrote to Charles Sayle on October 1, 1888 (New Letters, no. D1, pages 4–5):

There are, as you say, still books, dogs and little girls of seven years old in it but unhappily. One begins to yawn over the books and the dogs die and, oh Sayle, Sayle — the little girls grow up, and become those very objectionable animals, women.

That same exclusivity for girls before the “magical age 10” was expressed to Arthur Moore on June 30, 1889 (Letters, no. 53, page 88):

I think it possible for the feminine nature to be reasonably candid & simplex, up to the age of 8 or 9. Afterwards — phugh!

On August 27, 1890 (Letters, no. 113, page 162), rejoicing after the return of Adelaide from a trip, he said to Moore about the novel they were writing together:

I will even go back to Rainham & Mary Masters & all the other uninteresting adults one is foolish enough to write about. Why the deuce does any one write anything but books about children! Quelle dommage that the world isn't composed entirely of little girls from 6–12.

In 1889, Dowson made “experiments” of platonic love with two post-pubescent females (aged 13-19), first Lena, a barmaid, then Bertha van Raalte, the daughter of a tobacconist. But these relations did not last long; he was not really motivated, and tended to see children as superior beings. He had an ambiguous attitude towards women. He was sexually attracted to them but rejected them sentimentally. He confided his ideas to Arthur Moore on January 3, 1889 (Letters, no. 4, page 22):

Depend upon it there is something radically weak in a woman’s brain. One should only know them carnally — I doubt if one can know them otherwise.

[...] The biblical use of the word “know” — in reference to a woman is full of suggestion. [...] What a charming world it would be if they did not exist — or rather if they never grew into their teens. And yet it is a folly to try & escape from them. [...]

Or one might adopt a child & cease to trouble about them—only then she would grow up — (for of course it would be she — was there ever an unobjectionable small boy?—) & so one’s last state would be a million times worse than one’s first.

This contrast between his platonic worship of little girls and his cynical view of women probably reflects a deep-seated split in Victorian sexual mentality, between 'pure' (sentimental) love and sexual lust. Many of his sexual encounters likely occurred with prostitutes or women met in bars.

In a letter to Arthur Moore dated October 16, 1889, a few weeks before meeting Adelaide (Letters, no. 68, page 108), he associates women with debauchery and alcohol:

Mercifully my little sample with Swanton of an exhibition in a purlieu of Leicester Square so absolutely sickened me with the feminine nudity that my debauchery hasn’t since extended beyond the bottle.

Then he contrasts these women with the innocent beauty of a little girl, whose prototype is Minnie Terry:

I’ve been kissing my hand aimlessly from the window to une petite demoiselle of my acquaintance — also par exemple a Minnie & presque aussi gentille as her prototype. This has temporarily revived me.

Envisaging his breakfast and his dissatisfaction with whiskey and “phiz,” he adds:

there is nothing in the universe supportable save the novels of Hy. James [Henry James], & the society of little girls.

Loving Adelaide

In November 1889, Dowson entered a cheap Polish restaurant held by Joseph Foltinowicz, located at 19 Sherwood Street in Soho (London), at the back of the present Regent Palace Hotel. “I discovered it. It is cheap; the cuisine is fair; I am the whole clientele, and there is a little Polish demoiselle therein (Minnie at 5st 7 — not quite that) whom it is a pleasure to sit & look at.” (Letters, no. 73). The “little Polish demoiselle” was Adelaide, the proprietor’s daughter, aged 11 and a half years, whom he nicknamed “Missie” or “Missy”. He would soon fall in love with her and, quite unexpectedly, he would continue to love her as she grew into her teens (cf. the poem Growth). Although she rejected his marriage proposal and eventually married another man in 1897, his feelings for her did not abate.

Soon after Dowson met her, she became the center of his life. His first volume of poetry, Verses, includes Preface: For Adelaide, starting with the words “To you, who are my verses.” A few lines below we read “For I need not write your name for you at least to know that this and all my work is made for you in the first place.” Writing to Arthur Moore on February 16, 1890 (Letters, no. 89, pages 137–138), he presents her childhood as soothing the sufferings of his life:

Certainly the mere friendliness of a child has some such effect on me — seems to me at times to be not merely a set-off against one’s innumerable unliquidated claims against life but a quite final satisfaction of them — an absolute end in itself.

[...]

there is after all nothing so important as that one should be constantly trying to multiply these moments & to make them last.

Spending almost all evenings in this restaurant he called “Poland,” Dowson felt increasingly close to Adelaide, as one can read in his letters to Arthur Moore (Letters, no. 89, pages 137–138):

I dine almost invariably in Poland now. The atmosphere of the place has the most cheering effect on me. The dear child becomes daily more kind & gracious. The other day she came & sat by me & conversed with great affability all the time I was there. She really is the most quaint & engaging little lady—& she can play fiddle very prettily.

Then on March 4, 1890 (Letters, no. 92, page 140):

La pétite would not allow me to sit in my usual place but led me up above the salt to the fireside table You can imagine how “gratted & flattified” I was. [...] She is the most charming little chatterbox & we are quite on a footing of vieils amis by this time.

He took Adelaide out to various entertainments: theater shows, an “Egyptian” scene of magic, a panoramic show of the Niagara Falls, Madame Tussaud’s wax museum and Hengler’s circus; he also sent her the works of Lewis Carroll.

Like most Polish people, the Foltinowicz family were Catholic, and Dowson went to admire Adelaide when she participated in processions. He wrote to Moore on October 19, 1890 (Letters, no. 123, pages 172-173):

You ought to have come to N.D. de France tonight. There was a procession after Vespers of the Enfants de Marie & I just managed to discern my special Enfant in spite of her veil [...] It was a wonderful & beautiful situation: the church [...] the long line of graceful little girls all with their white veils over their heads [...] Childrens voices in concert are wonderful! Children’s voices exercised in the “Ave Maris Stella”, are the most beautiful things in the world.

Flower and Maas conclude the Introduction to Part II of Letters (1967) with the following (page 128):

Though she probably never knew it, Adelaide was the inspiration of almost all Dowson’s best work. During these years the clouds were already beginning to hang upon their relationship, but she remained none the less his chief source of happiness—perhaps the only one.

Dowson decided to propose to Adelaide by her 14th birthday, but struggled with nerves, indecision, and being rejected by multiple employers while the income from his family's business declined. Afraid he would lose his chance to be with a female he had loved and remained attracted to, he explained his resolution to Moore in January 1892 (Letters, no. 173, page 221):

I will put an end to this absurd pretense of further consideration which deceives nobody and plainly declare myself. [...] I do not believe in marriage in the abstract in the least. Only it is the price, perhaps a heavy one, which one is ordered to pay [...] In the present case I would pay it ten times over, sooner than risk the possibility of some time or other regretting that I had let go irrevocably something which promised a good deal, which I never had, & which is perhaps after all the best thing obtainable in this stupid world

However, he would have to be in a position to support Adelaide and offer her a home if he were to expect his proposal to be accepted. The situation was complicated by the declining health of Joseph Foltinowicz, Adelaide’s father, and he proposed at what Flower and Maas describe as "the worst time" - just after Adelaide's father died. Dowson thought he would be too nervous to propose until Adelaide reached 17, and recalled that she was not surprised or angry with him after his proposal, but thought he should have waited until she was older. After Dowson's parents committed suicide, Dowson was embroiled in legal battles to obtain inheritance and was rejected by a 3rd employer. Being continually rejected, London became intolerable and he left. Living mostly in France, he still exchanged letters with Adelaide (Letters, no. 335, page 362: To Victor Plarr, May 1896):

Missie writes to me fairly often, friendly letters, which give me sleepless nights and cause me to shed morbid and puerile tears.

And (Letters, no. 343, page 369: To Arthur Moore, June 1896)

I have broken my heart over her, but she remains, none the less, my sole interest in life.

He sent a friend to attend Adelaide's wedding, bringing a present in place of him.[8]

Oscar Wilde and Dowson

Dowson and Oscar Wilde were good friends and their relationship deepened after Dowson's series of life crises / rejections. When Wilde, friend to non-exclusive pederast Andre Gide, and traveler to Capri, the Italian island once frequented by many famous gay/pederast writers such as Norman Douglas and Jacques d'Adelsward-Fersen - was jailed in 1895 for homosexual behavior - Dowson was one of the few of his friends who remained faithful to him. As Flower and Maas (page 377) write:

It took some courage for anyone to be seen with Wilde in 1897; most of the friends who had been proud to know the eminent author in his successful days now coldly ignored his existence. Dowson was one of the few who did not abandon him, and his action in seeking out the ostracized poet is evidence of that generosity and charm to which all his friends have borne witness. Wilde’s friendship was the best possible thing for Dowson.

Upon his release in 1897, Wilde continued to cultivate his friendship with Dowson, whose poetry he loved. On June 15, 1897, Wilde wrote to Dowson (Letters, Introduction to Part V, page 377):

Why are you so persistently and perversely wonderful?

Then on June 28:

I write a little line . . . to tell you how charming you are . . . Tonight I am going to read your poems—your lovely lyrics—words with wings you write always. It is an exquisite gift, and fortunately rare in an age whose prose is more poetic than its poetry.

On February 18, 1898, Wilde wrote to their publisher and friend Leonard Smithers (Letters, Introduction to Part V, page 380):

I am so glad you are coming over alone. I don’t want to be bored with Mrs Dowson. Ernest is charming, but I would sooner be with you alone, or with him along with you.

From this, scholars Flower and Maas infer that Dowson probably had a regular mistress, whom Wilde disliked. Even so, upon hearing of Dowson's death, Wilde wrote to Smithers from Paris:

Poor wounded wonderful fellow that he was, a tragic reproduction of all tragic poetry, like a symbol, or a scene. I hope bay leaves will be laid on his tomb and rue and myrtle too for he knew what love was.

Legacy

The phrase "Gone with the wind", comes from his poem Non Sum Qualis eram Bonae Sub Regno Cynarae".

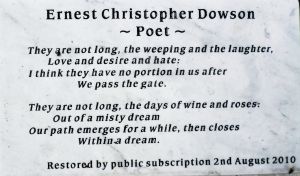

Dowson's gravestone was restored on August 2, 2010, on the 143rd anniversary of Dowson’s birth.[9] The new gravestone includes a plaque which added his most well-known poetry verse:

They are not long, the days of wine and roses:

Out of a misty dream

Our path emerges for a while, then closes

Within a dream.

– From "Vitae Summa Brevis" (1896)

References

- ↑ Wikipedia on the Decadent movement.

- ↑ Ernest Dowson: Verses, in Ernest Dowson Collected Poems, R. K. R. Thornton with Caroline Dowson (editors), University of Birmingham Press (2003). Also in The Poems and Prose of Ernest Dowson, With a Memoir by Arthur Symons, Project Gutenberg Ebook.

- ↑ The Letters of Ernest Dowson, Desmond Flower and Henry Maas (editors), Fairleigh Dickinson University Press (1967).

- ↑ New Letters from Ernest Dowson, Desmond Flower (editor), The Whittington Press (1984).

- ↑ Wikipedia on the Rhymers' Club.

- ↑ According to Hugues Lebailly’s article “Charles Dodgson and the Victorian Cult of the Child“, The Carrollian, The Lewis Carroll Journal, no. 4, autumn 1999, pp. 3–31: Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) noted in his Diaries on Monday 2 July 1888 that he felt “a little disappointed” with Minnie Terry’s ‘Mignon’ in Bootle’s Baby, deploring that she “recite[d] her speeches, not very clearly, without looking at the person addressed”.

- ↑ Most of the information for this section comes from Ernest Dowson and the Cult of Minnie Terry. (2015). pigtailsinpaint.org

- ↑ Click for a fuller account.

- ↑ On Dowson's grave restoration.