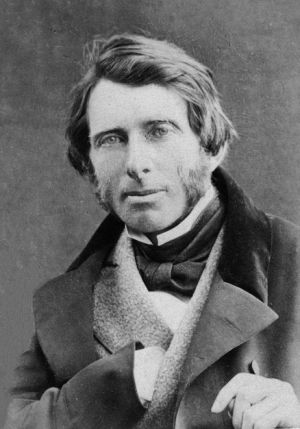

John Ruskin

John Ruskin (born February 8, 1819, London, England — died January 20, 1900, Coniston, Lancashire) was an English writer, philosopher, art critic and polymath of the Victorian era. Britanicca describes him as an "English critic of art, architecture, and society who was a gifted painter, a distinctive prose stylist, and an important example of the Victorian Sage, or Prophet: a writer of polemical prose who seeks to cause widespread cultural and social change".[1] Famous writer Leo Tolstoy described him as “one of the most remarkable men not only of England and of our generation, but of all countries and times”[2], and historical scholarship evidences the case that Ruskin was a celibate MAP similar to Lewis Carroll, who remains a highly influential and celebrated figure.

John Ruskin was a MAP (Minor Attracted Person)

Ruskin was predominantly sexually/romantically attracted to females around the ages of 10 to 16, writing in a letter to his physician John Simon on 15 May 1886, (quoted in Burd, 2007)[3]:

But I [Ruskin] like my girls from ten to sixteen–allowing of 17 or 18 as long as they’re not in love with anybody but me.–I’ve got some darlings of 8–12–14–just now, and my pigwiggina here–12–who fetches my wood and is learning to play my bells.

In a letter to illustrator Kate Greenaway, Ruskin playfully requested nude drawings of little girls (Engen, 1981, p. 94)[4]:

Will you – (it’s all for your own good – !) make her stand up and then draw her for me without a cap – and, without her shoes, – (because of the heels) and without her mittens, and without her – frock and frills? And let me see exactly how tall she is – and – how – round. It will be so good of and for you – And to and for me.

In Italy, 46-year-old Ruskin was moved by the sight of a half-naked ten-year-old girl (Hilton, 2002, p. 253)[5]:

One of the finest things I saw at Turin was a group of neglected children at play on a heap of sand — one girl of about ten, with her black hair over her eyes and half naked, bare-limbed to above the knees, and beautifully limbed, lying on the sand like a snake...

The image affected him so much that he would still mention it in diaries and lectures decades later. Another somewhat erotic description of the event appears in his The Cestus of Aglaia (Ruskin, 1911, p. 145)[6]:

the image of an Italian child, lying, she also, upon a hill of sand, by Eridanus’ side; a vision which has never quite left me since I saw it. A girl of ten or twelve, it might be […] She was lying with her arms thrown back over her head, all languid and lax, on an earth-heap by the river-side, (the softness of the dust being the only softness she had ever known), in the southern suburb of Turin, one golden afternoon in August, years ago. [...] The sand was mixed with the draggled locks of her black hair, and some of it sprinkled over her face and body, in an “ashes to ashes” kind of way; a few black rags about her loins, but her limbs nearly bare, and her little breasts, scarce dimpled yet, white, marble-like but, as wasted marble, thin with the scorching and the rains of Time.

Ruskin's marriage and Rose La Touche

Ruskin’s one marriage to Effie Gray[7] fell apart after he saw his wife’s nude body, which disgusted him. Their marriage was annulled after six years owing to non-consummation. By contrast, Ruskin met nine-year-old Rose La Touche in 1858 at the age of 39, became her tutor at the request of her mother Maria La Touche, and soon thereafter fell in love. His autobiography suggests that he fell in love by 1860 at the latest, when Rose would have been about eleven (Ruskin, 2012, p. 364[8]; note this passage was omitted from the original publication):

And in the year 1860 the ‘new epoch of life,’ above spoken of, began for me in this wise, that my father and mother could travel with me no more, but Rose, in heart, was with me always, and all I did was for her sake. [...] I recollect an American – not friend, but the intimate companion – asking me who Rosie-Posie was, – the words sometimes being said aloud unconsciously. Then in 1860, I could not bear being so far away from her.

When Rose moved away in 1862, Ruskin wrote: “They took the child away from me — . . . and since that day of April 1862, I have never had one happy hour, — all my work has been wrecked — all my usefulness taken from me . . .” (Hilton, 2002, p. 321). Ruskin would carry letters from Rose in his breast pocket, the first of which was sent when she was thirteen (Hilton, 2002, p. 312). He also reprinted this first letter in his autobiography, alongside an account of their meeting (Ruskin, 1907)[9]:

So presently the drawing-room door opened, and Rosie came in, quietly taking stock of me with her blue eyes as she walked across the room; gave me her hand, as a good dog gives its paw, and then stood a little back. Nine years old, on 3rd January, 1858, thus now rising towards ten; neither tall nor short for her age; a little stiff in her way of standing. The eyes rather deep blue at that time, and fuller and softer than afterwards. Lips perfectly lovely in profile ; — a little too wide, and hard in edge, seen in front ; the rest of the features what a fair, well-bred Irish girl’s usually are; the hair, perhaps, more graceful in short curl round the forehead, and softer than one sees often, in the close-bound tresses above the neck. [...] Some wise, and prettily mannered, people have told me I shouldn’t say anything about Rosie at all. But I am too old now to take advice, and I won’t have this following letter — the first she ever wrote me — moulder away, when I can read it no more, lost to all loving hearts.

He waited until Rose was around 18 before proposing to her (and was eventually rejected). Ruskin had met Rose at a time when his own religious faith was under strain, which caused difficulties for the staunchly Protestant La Touche family who at various times prevented the two from meeting. A chance meeting at the Royal Academy in 1869 was one of the few occasions they came into personal contact. After a long illness, Rose died on 25 May 1875, at the age of 27. These events plunged Ruskin into despair and led to increasingly severe bouts of mental illness involving a number of breakdowns and delirious visions.

Ruskin convinced himself that the Renaissance painter Vittore Carpaccio[10] had included portraits of Rose in his paintings of the life of Saint Ursula.[11] He also took solace in Spiritualism, trying to contact Rose's spirit.

Rose and Ruskin's romance is alluded to in Ruskin's small tract on education and culture, Sesame and Lilies (1865). According to Wolfgang Kemp "the whole work is riddled with allusions and direct references to the la Touches."[12]

Ruskin's legacy

Ruskin's influence reached across the world. Marcel Proust not only admired Ruskin but helped translate his works into French.[13] Mahatma Gandhi wrote of the "magic spell" cast on him by Unto This Last and paraphrased the work in Gujarati, calling it Sarvodaya, "The Advancement of All". In Japan, Ryuzo Mikimoto actively collaborated in Ruskin's translation. He commissioned sculptures and sundry commemorative items, and incorporated Ruskinian rose motifs in the jewellery produced by his cultured pearl empire. He established the Ruskin Society of Tokyo and his children built a dedicated library to house his Ruskin collection.[14]

Ruskin was an inspiration for many Christian socialists,[15], and a number of utopian socialist Ruskin Colonies attempted to put his political ideals into practice. These communities included Ruskin, Florida, Ruskin, British Columbia and the Ruskin Commonwealth Association, a colony in Dickson County, Tennessee in existence from 1894 to 1899. Edward Carpenter's community in Millthorpe, Derbyshire was partly inspired by Ruskin.

Future British Prime Minister Clement Attlee acknowledged their debt to Ruskin as they helped to found the British welfare state, and more of the British Labour Party's earliest MPs acknowledged Ruskin's influence than mentioned Karl Marx.[16]

Writers as diverse as Oscar Wilde, G. K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc, T. S. Eliot, W. B. Yeats and Ezra Pound felt Ruskin's influence.[17] Ruskin is also credited by the Oxford English Dictionary with creating the first quotation, and thus definitions, of in 152 separate entries, include important literary terms like pathetic fallacy.

Ruskin's ideas on the preservation of open spaces and the conservation of historic buildings and places inspired his friends Octavia Hill and Hardwicke Rawnsley to help found the UK National Trust.

In 2019, Ruskin200 was inaugurated as a year-long celebration marking the bicentenary of Ruskin's birth. Admirers and scholars of Ruskin can visit the Ruskin Library at Lancaster University, Ruskin's home, Brantwood, and the Ruskin Museum, both in Coniston in the English Lake District. All three mount regular exhibitions open to the public all the year round.

See also

References

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Ruskin

- ↑ Stuart Eagles, Ruskin and Tolstoy (2nd edn) (Guild of St George, 2016) p. 12.

- ↑ Burd V. A. (2007). “Ruskin on His Sexuality: A Lost Source,” Philological Quarterly, 86 (4): 433.

- ↑ Engen R. K. (1981). Kate Greenaway: A Biography. Schocken Books, p. 94.

- ↑ Hilton T. (2002). John Ruskin. Yale University Press.

- ↑ Ruskin J. (1911). The crown of wild olive, and The cestus of Aglaia. London: J. M. Dent & Sons.

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Effie_Gray

- ↑ Ruskin J. (2012). Praeterita. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Ruskin J. (1907). Praeterita, Vol. III. London: George Allen.

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vittore_Carpaccio

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Ursula

- ↑ Kemp, Wolfgang. The Desire of My Eyes: The Life and Work of John Ruskin. 1990. pp. 296–297

- ↑ Cynthia J. Gamble, Proust as Interpreter of Ruskin. The Seven Lamps of Translation (Summa Publications, 2002)

- ↑ Masami Kimura, "Japanese Interest in Ruskin: Some Historical Trends" in Robert E. Rhodes and Del Ivan Janik (eds.), Studies in Ruskin: Essays in Honor of Van Akin Burd (Ohio University Press, 1982), pp. 215–44; Catalogue of the Ryuzo Mikimoto Collection: Ruskin Library, Tokyo 2004.

- ↑ Gill Cockram, Ruskin and Social Reform: Ethics and Economics in the Victorian Age (Tauris, 2007)

- ↑ Stuart Eagles, After Ruskin: The social and political legacies of a Victorian prophet, 1870–1920 (Oxford University Press, 2011) and Dinah Birch (ed.), Ruskin and the Dawn of the Modern (Oxford University Press, 1999).

- ↑ W. G. Collingwood, Life and Work of John Ruskin (Methuen, 1900) p. 260.